This is my last pre-election post, and hopefully my last about politics for quite a while. It’s long and I apologize, but please bear with me.

Almost everyone I know complains that our campaigns are conducted largely through negative, personally-oriented TV ads and that our elected officials pursue the agendas of some set of “special interests” that are not the interests of the American people. Let’s look at both complaints, and let’s start with a true story.

In 1982, I managed a campaign that resulted in my candidate getting elected to the US House of Representatives. The primary was the entire race, and my candidate was the sane guy – a moderate Republican, very much in line with the sentiments of the district. Our chief rival was the chairman of the legislature’s redistricting committee and had gerrymandered the most Republican district he could. He also was a right-wing nut. By that I do not mean one of the Pauls – Rand or Ryan. I mean he was a nut. That fact notwithstanding, he was well-funded and had unlimited access to direct mail.

We spent months participating in debates, courting the press, and generally trying to foster a reasonably serious discussion of issues. Had anyone paid attention, that would have worked in our favor because while my guy had his flaws, he wasn’t a nut. But no one paid attention. The other guy saturated the district with schlocky, fact-distorting direct mail and piled up a big lead.

In the waning days of the campaign, we turned that around by taking advantage of the local papers’ discovery of the other guy’s business relationship with the firm that sent out all the direct mail on his behalf. I won’t go into how they made that discovery, but will say that after largely ignoring the race for months, both papers reported this juicy story on the front page, above the fold. We used their coverage as the basis for a 30-second radio ad, the first 15 seconds of which were brutally negative, if reasonably justified. That ad stopped and then reversed our opponent’s momentum and gave us the win. It was the only thing we did that people actually paid attention to.

This is how campaigns actually work, and there’s a lesson in it. The reason political campaigns are dominated by half-truths, distortions and negative ads is that those things work. If other things worked better, the campaigns would do them instead. The don’t-go-below-the-surface arguments, the presentation of goals as if they were plans, the distortions of facts and the personal attacks – these are the things to which the electorate pays attention and responds.

“The electorate,” by the way, includes you and me.

As to the agenda of our elected officials, here’s another bit of bad news. It’s easy to rail at the rascals, to blame our problems on low-caliber elected officials, lack of leadership and the impact of money. Easy, but mostly wrong. Again, a bit of personal experience:

After the campaign I described above, I moved to Washington, DC, and spent two years as a legislative assistant to a member of the US Senate, where I got to see the sausage factory from the inside. I can attest that all of the dynamics that we complain about now were fully in place then. There used to be a higher degree of cordiality – people on opposite sides of the aisle often were friends and could talk to each other. That seems largely to have disappeared. The volume was turned up and the elbows sharpened in 1994, when Newt Gingrich discovered C-SPAN. And the flood of money unleashed by Citizens United has turned the volume up even further.

But that doesn’t mean the Congress of 30 years ago somehow was better at solving problems than the Congress of today. Indeed, the underlying dynamics have not changed. Regarding money, except in the case of abjectly corrupt officials – the kind who have stacks of cash in their freezers – money will get you a meeting, but it won’t get you a vote. Money flows to candidates whom the moneyed interests expect will be inclined to support them. That money goes to fund the negative ads we complain about, then use to make our decisions. We eat the dog food.

There’s a structural problem here as well. The Founding Fathers did a brilliant job of designing institutions that would apportion growing resources more or less fairly over time. Those institutions, however, were not designed, and do not have the capacity, to apportion the pain of slower-growing, let alone declining, resources. That’s why every difficult choice gets thrown to a commission, or Congress puts in place a self-destruct mechanism like the so-called fiscal cliff.

The reason Congress can’t make those tough calls is that it is astoundingly responsive to the short-term will and wishes of the American people. The parties poll incessantly, so they know what we think, however irrational or poorly informed we may be (for example, something like 70% of people who identify themselves as Tea Party voters oppose cuts in Medicare and Social Security). I know this will come as a shock, so you may want to sit down, but Congressmen vote in ways that they anticipate will keep them in office. The rationale is, “If I’m not here, I can’t do any good, so I’ll say what I need to and vote how I need to in order to make sure I stick around.”

In short, however much we may complain about it, the government we have is exactly the government we want. We could throw all the bums out, and within six months, the new bums would be behaving just like the old bums because we, their customers, tell them what kind of dog food we want.

This is not a game. We have serious issues to address. I took the picture below at a Starbucks. As best I can tell, proceeds from the sale of these bracelets go into a fund that makes micro-loans to American manufacturers.

Micro-lending is the province of third-world countries. Just down the street from this Starbucks is a large building that used to be a luxury furniture store. Today, it is a thrift shop.

However much you may believe in American exceptionalism, it is worth remembering that exceptionalism often requires hard choices and sacrifice, neither of which have we been willing to make.

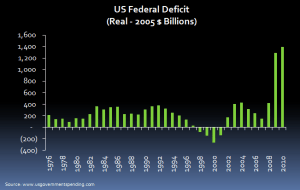

This following graph is from a presentation I gave in 2010 called “Economic Realities of the New Normal.” It shows the history of the US balance of trade over the past 50 years.

While many factors go into the balance of trade, at the highest level it tells us whether we want to buy more of their stuff or they want to buy more of our stuff. The answer is obvious, and tells us that the US economy has been fundamentally non-competitive for the past 37 years. This is an inconvenient and unpleasant fact, but a fact nonetheless.

For that entire time, we have consumed more than we’ve produced. Consumption feels good, but you have to pay for it somehow. We’ve done that largely by borrowing back the money we sent to foreign countries to buy their stuff, so that we could buy more of their stuff. Wash, rinse, repeat.

The biggest portion of that borrowing is Federal debt (this graph doesn’t show it, but the total Federal debt is now over $16 trillion, about two-thirds of which has been borrowed from offshore because that’s where the money is.)

When I was living in Washington, DC, I heard George Will give a talk. One thing he said that stuck with me is that our fiscal problem is that “every year the American people want $300 billion of services from their government that they’re not willing to pay for.” He said that in 1983. A quick look at the graph above shows that he was right, except that we did better in the late Clinton years, and that today, $300 billion has turned into $1 trillion. (Before my more conservative friends get exercised over Obama and the twin towers on the right, of which two more have now been added, it is worth remembering that the first of those towers belongs to George W. Bush.)

The “American people” who simultaneously demand and refuse to pay for those services include you and me.

And the graph above doesn’t tell the entire story. To generate cash, we’ve conducted a national garage sale, selling off a net $4 trillion of assets (companies, real estate, etc.). We’ve generated phantom wealth through a tech frenzy and a real estate frenzy. States, localities and individuals have borrowed even more. Total US non-corporate debt is around $22-23 trillion, which means that about one-third of all the capital in the world has been borrowed by. . .us.

In my childhood, my father introduced me to Pogo, Walt Kelly’s swamp cat who had a way of malapropping his way to the truth. He knows who dealt this mess, and I can’t say it better than he did.

It is far easier to blame the bums and the big money than it is to hold ourselves accountable. But change starts with accountability. It is too late to get better choices for this year. But it is not too late to remember that we are the market to whom this stuff is being sold. The only way we will get better candidates, better choices and better outcomes is to stop paying attention to the nonsense and start demanding honesty about the challenges we really face and the difficult choices we have to make.

Amen! We’ve gotten exactly what we asked for. Moreover, we keep reinstating Senators and Reps who given their age, capture, and inculcation can’t break the mold. It might be time to vote for new people, regardless of their stated positions…it’s hard to imagine that would make things worse.

As I watched reporting on Sandy’s aftermath the #1 comment was a version of “where is my government? Why isn’t it here to help me?” I bet several of these people also vote for lower taxes, smaller government and agree with a candidate to dismantle FEMA.

There is no way people know what is true, what isn’t, or what is distorted. Answer – create a panel that must approve the legitimacy of all ads; a group that creates rules for political ads and enforces those rules with fines and incarceration for lying. Or eliminate political advertising and require all information be direct – such as web sites, etc. I cannot accept that intentional lying and half-truthing is inherently part of the process that cannot be eliminated.

I would vote for prohibiting both polling and advertising – forcing the discussion into more depth. Naive and impractical, but it would make manipulation harder.

Unfortunately the most exceptional thing about the US today is how we have a population that is willfully ignorant about things beyond every football or baseball statistic and ensuring they get theirs while thinking that anyone else who wants something is a taker. As Dan says, 70% of Tea Party members want to end government but still expect to get their Medicare.

We have become the biggest warmongering nation with all its costs while others spend their resources on expanding education, migrating to renewable energy (Saudi Arabia has set the goal of 2025…I think…for being totally on renewables, and creating engineers rather than financial manipulators.

As usual, Pogo is right.

My favorite argument of this (and every other) political season: Candidate X lied in his/her ad (a good example is the recent Romney/Jeep ad). The only people who know or care whether it is a lie or not are the ones that decided a long time ago who they are voting for.

Dan, I usually find myself agreeing with the stuff you write, and I agreed with some of what you wrote this time with these notable exceptions:

“money will get you a meeting, but it won’t get you a vote.” Sorry, but I think that’s exactly what money gets you. And further down in your blog, you seemed to agree with me.

“If I’m not here, I can’t do any good, so I’ll say what I need to and vote how I need to in order to make sure I stick around.” But to stick around, I need money. And with the advent of SuperPacs and the Supreme Court decision that corporations are people too, I don’t need just a little money, I need boatloads of it. So how do I get the money I need to make sure I stick around? As you’ve said above, “I’ll vote how I need to” to keep my benefactors happy and keep that cash coming.

“In short, however much we may complain about it, the government we have is exactly the government we want.” Of course, speaking only for myself, no way are the dysfunctional institutions in Washington the government I want! And since Congress is enjoying the lowest approval ratings in anyone’s memory (maybe ever), I’d say I have some company with that view.

Now will you please get off your soapbox and get back to work?

Great comments, Andy, and much appreciated. People have been complaining about money in politics for a long time. It was Will Rogers who said, “We have the best Congress money can buy.” That said, today, TV advertising consumes most of the money, and the press covers the ads as if the ads themselves were news. Imagine seeing this on CNBC: “McDonald’s released a new ad today claiming unique taste virtues of the McRib. Burger King immediately denounced the ad as false and misleading.” It would be silly, but that’s the presidential race.

I think the place where you and I differ is in the calculus of “voting in a way that will keep me in office.” Granted, it’s been a long time since I was there, but my experience was that those votes are cast with the electorate, not the money, in mind. The best example – 30 years ago, EVERYONE understood that the core entitlement programs were unsustainable, but no one would say so publicly, much less vote that way. They weren’t afraid of offending their financial backers. They were afraid of incurring the wrath of AARP.

That was my perspective at the time. Perhaps it has changed, but I don’t think so. There was (and from what I can tell, still is) enormous consensus about some very fundamental issues – i.e., everyone understands that the only way to address the deficit (other than massive inflation) is something like Simpson-Bowles. But no one wants to say it because they fear, justifiably, that an uninformed, short-sighted electorate will throw them out of office.

And your last point is my point exactly. Those dysfunctional people and institutions aren’t the government I want either. But we (collectively) keep electing them and putting them in a position from which they will never be able to make the hard choices we need them to make. Thus, in my view, more our fault than “theirs.”

My soapbox is very tall. Looking for a ladder with which to climb off it!

OK Dan, I like the way you think. I also like that Facebook calls it the “Wall”. We are talking to the wall. Suppose we decided that we’d talked to the wall long enough, then would we actually like to do something about the problems? In your experience, how could we pursue real change vs (or in addition to) wall talk?

A very smart guy I know always tells me, “The question to ask is not ‘Why can’t we?’ but rather, ‘How could we. . .?'” I find this extraordinarily annoying, mostly because it is undeniably right.

I’ll have to work on this because hoping that the American people will somehow become better-informed and longer-sighted is, admittedly, a bit of a pipe dream.